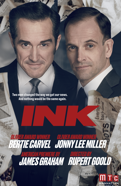

Ink's Tony-Nominated Scribe James Graham on Rupert Murdoch's Indelible Mark on the Media

(Photographed by Caitlin McNaney for Broadway.com)

British scribe James Graham has never been one to shy away from topical subjects. His plays Privacy and The Vote, for example, delve into the personal and the political in real time. Now, with his Tony-nominated drama Ink, Graham is unearthing the origin story of Rupert Murdoch’s tabloid The Sun, and how it may have given birth to today’s toxic media environment, which has risen to new heights of ignominy. Graham sat down with Broadway.com to chat about his “sparkle of mischievousness,” what he was doing when Murdoch came to the show, and why he doesn’t want the media mogul to like his play too much.

Where did this play come from?

I was out drinking lots of whiskey, and I thought, “Why don't you recklessly put Rupert Murdoch on stage?” No! I always knew the story of a rivalry between these two papers, The Sun and The Mirror in the '60s. I've always really enjoyed self-contained worlds and trying to make sense of Britain by looking at a system or structure. So, I always thought about newspapers, but then about three years ago, I started to have huge anxieties about the way news was changing.

(Photo: Joan Marcus)

What caused the anxiety?

Our referendum and your presidential election—and just social media and how our conversation was changing. It felt like it was getting more toxic and quite brutal and often lacking empathy. The emergence of populism in government and in everything. I wanted to do an origin story about maybe when that started to shift. It felt like it just made sense to go back to when Rupert Murdoch arrived on Fleet Street.

What is it about these figures that appealed to you?

I don't want to make it sound too political. But on a political level, I was interested in walking through the footsteps of people who created something that I don't necessarily agree with, and that, I think, has had some negative outcomes on our news media. I wanted to try to play devil's advocate with my own prejudices, and go, “What did they think they were doing?” The Sun became the most popular paper in the English-speaking world, and Fox News is one of the most successful broadcast news media in the U.S., so it's appealing to somebody. I ask the question, in as generous a way as possible, “What is it that attracts people to it?” And then prosecute it, asking, “What are the dangers of that kind of news media?” I also wanted to try and insert into that cultural and political conversation a human story about a character and in the form of the character of Larry Lamb. He is someone who most people in the U.K. would never have heard of—I'd never really heard of him. But I think his influence in deciding what The Sun would be, and therefore what most modern newspapers would be, is extraordinary.

Were you drawn by his transformation?

Yes, I wanted to go on his journey because he didn't start out from that place where he ends up at the end of the play, at the end of his life. He was an ardent Thatcherite, Reaganite, free marketeer—he would speak in the vein of Fox News. But he started off as someone who described himself as a socialist, who would describe himself as left wing and came from the collectivist community background in the north of England. That journey, spiritually and ethically and emotionally, I wanted to look at, and what might tempt somebody to leave all that behind and change their stripes.

How hesitant were you to put Rupert Murdoch on stage when he is such a lion of the media all over the world, particularly in the U.K. and the U.S.?

I don't mind saying I was quite nervous about it, partly because no one had ever put him in a play before that I'm aware of. There have been characters in TV dramas and plays that felt like it may be a version of him, but this is putting his biography and his name and words into his mouth on stage. These papers are very powerful, and I didn't know whether they would support the endeavor or be welcoming of it. Like, brutally, you always have to speak to loads of lawyers about the risk of litigious action against you for misrepresenting someone's character. And these are very powerful people. [I’m] not saying he would have done, but that was in my mind.

Were there other concerns?

As a writer, I’m someone who tries to—rightly or wrongly—have balance, if such a thing even exists in looking at and portraying people, and particularly political voices who I might disagree with, but want to try and find a humane, empathetic way present on stage. I was nervous about that because I don't mind admitting Murdoch's politics are not my politics. Also, honestly, there’s a little sparkle of mischievousness and recklessness in me, so I thought, “Why not?” I like being a bit scared. I like getting a script back from the lawyers, which is covered in red, saying, “You've got to be really careful here. This is very dangerous. How many sources do you have for this?” That kind of thing. You sort of start to realize, “F**k, I might be doing something that's quite on the edge.”

Tell me why you had an interest in the rivalry between The Sun and The Mirror in the first place.

It's one of those things where when you're researching one thing, and you come across something else. I think I was probably researching another play, and I came across a bizarre story, which actually hasn't featured in the play—we tried, but it didn't work—in the first year of The Sun. The rivalry between the two reporters got so intense and extreme that it manifested itself in this really bizarre way, which was they eventually decided to both come down from their offices onto the street and have a hopping race down Fleet Street.

A hopping race?

As in, when you hop on one foot. It was the manifestation of something that felt obviously bizarre and weird and extreme. I wanted to get to the bottom of what would make two people, two sides of the same argument, do that.

That's a crazy story.

It’s folklore, but I knew about the stealing, the cheating and the intense rivalry. Out of that narrative, I found a useful vehicle to try and interrogate some of these themes about populism and how it affects our news media, and how reflecting people back to themselves can have its benefits and attractions, but also its dangers.

It was reported that Rupert Murdoch recently came to see the show.

Yeah.

What was the stage manager’s report like from that night?

Ha! I heard it was a really terrible show. I think something happens in an audience when everybody's become suddenly aware that a character on stage is watching it from the auditorium. So, it was one of our quietest shows. I think everyone was just really tense.

Were you there?

No, but I was there when he came to see it in London. I couldn't bear to sit in the auditorium when he was watching it, but I did go and meet him afterward.

So, where were you while Rupert Murdoch was watching your play?

I was in the pub having several whiskeys. Trying to calm down. And then I waited backstage. I felt that if he was willing to come and listen to some arguments against his worldview, then I should then probably listen to his arguments back. That felt right. In the end, he didn't have any. Look, he's not the main character in the play; he's a secondary character. So, he came back, and I met him. He had a few questions, some concerns, but nothing that frightened me. I don't mind saying that I don't want him to like it too much because then I haven't done my job. I want him to be uncomfortable with some of it.